Between Ginza, the most prosperous district of Tokyo, and Tsukiji, the location of the biggest fish market in the world, there is a block called "East Ginza", which is the starting point for Mao Danqing's life in Japan and also the source of inspiration for him later to write in Japanese. There, he immerses himself in the daily life of ordinary Japanese and deal with all kinds of people, which has made him feel deeply the shock and surprise brought by the cultural differences.

Mao Danqing.

At the very beginning of our dialogue, Mao Danqing mentioned that his writing career was not typical as other writers'. He divided his 30 years of experience in Japan into three stages. For the first 10 years, he dropped out of school and went into business. In the next 10 years, he abandoned his business and turned to literature; during this period of time, he traveled throughout 47 prefectures in Japan and finished his first book in Japanese, which won 28th Bleu Mer Literary Prize in Japan and had appeared for many times in Japan's college entrance examinations. Then, for the third 10 years, he became a college professor, teaching Chinese in Japan. It is these special experiences that have formed his own way of thinking.

Among the Japanese students Mao Danqing taught, some became well-known Sinologists and some held important positions in the Japanese Foreign Ministry, invariably having close ties with China. Even all those years later, what they remembered was not a word or a pronunciation in the class but the inspiration that had come from Mao to learn Chinese and the ability to love the language.

With profound changes that have been ongoing in international relations, attention on China has been growing by the day from the rest of world. There are various ways to know China, one of which of course is through learning Chinese. As Mao Danqing once told his students: "By learning a language, you can understand the country and its culture, which can help enrich your own wisdom at the same time." For him, "Understanding others should always be more important than expressing ourselves."

Sometimes Mao shares Chinese compositions written by Japanese students on his Wechat account. In Mao's writing classes, instead of asking his students to focus on subjects only about China, he prefers asking them to write about various topics, such as the best scenery they have ever seen. One of the most frequently given advice by Mao to his students is "when you go to China, I hope you can still feel the local scenery in the same way as when you see a piece of beautiful scenery anywhere else."

Mao Danqing poses for a photo with students from Japan and Italy.

Indeed, his stay in Japan for over three decades is the best proof, as it has shown a feasible way to learn a foreign language: Language education is more on understanding the culture and touch the feelings of the people, not simply the logic and mechanics of language itself.

Each language has its own system, its unique expression habits and way of thinking. Learning language is the most effective way to understand the habits and the thinking of another culture, which usually takes a long time.

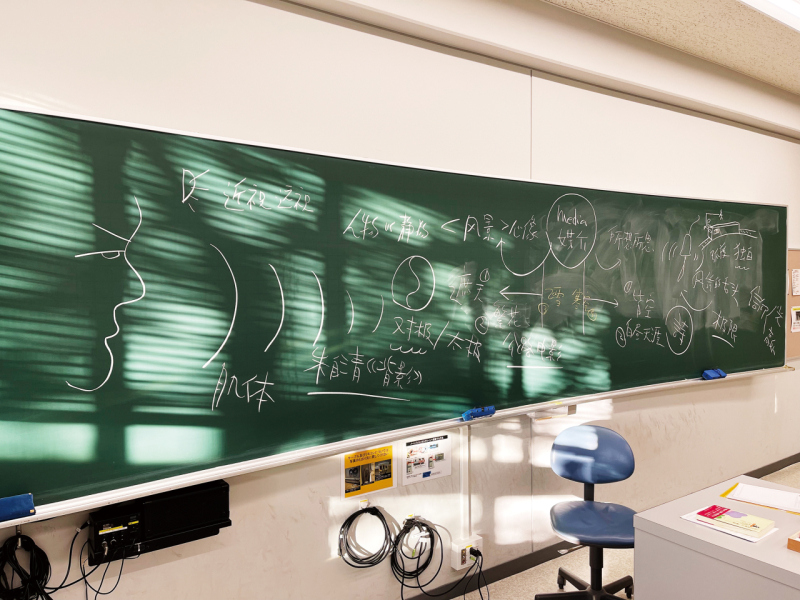

Mao Danqing has noticed an interesting point in the compositions that the Japanese students have written. Although finished in Chinese, the underlying thinking is still in Japanese. Looking back on the excitement, the doubt, the feeling of loss and the sudden enlightenment he has experienced in the process of studying Japanese, Mao compares learning a second language to a boxing match, an attrition game no less. Generally, in the second year, one will feel very excited that new words, expressions and sentences enter into one's mind so quickly and easily. However, in the third year, the progress often stagnates suddenly. What's worse is that as one becomes more and more immersed into the foreign language, he or she will see that their ability to speak mother tongue would be weakened. To Mao, this is when the two languages start to be engaged in a seesaw battle.

Blackboard writing for teaching Japanese students the Chinese language.

To smoothly get past this stage, Mao's suggestion is "to put the foreign language aside temporarily and strengthen the mother tongue. Taking Chinese as an example, learners should strengthen familiarity with poetry, increase the amount of reading and practice with exercises to find the root, so to speak, of the language. After all of these efforts, they can turn back to the foreign language study again, and then they could use it freely." To Mao, after going through this process, one will find that different languages could actually blended into each other.

Both a "young" and an "old" phrase, shouhui or "freehand sketching" exists both in Chinese and Japanese. Using this common expression in two cultures could help enhance mutual understanding in cross-cultural exchanges. Popular with his students, freehand sketching can be commonly seen in Mao Danqing's teaching materials and works. As time goes on, his students also begin to use freehand sketching on the class feedback cards to express their feelings.

Mao Danqing celebrates the 2002 Chinese New Year with Mo Yan and Kenzaburo Oe in Gaomi city, Shandong province.

Nowadays, with COVID-19 still going on, international cultural exchanges declined as a result, and it is no exception when it comes to China and Japan. Mao believed that more efforts should be made on "text-based communication" to promote cultural exchange.

For instance, apart from his teaching the Chinese language and writing books, he has translated a series of nonfiction books on Japanese women in the workplace for the Shanghai Translation Publishing House and established good relations with some well-known Japanese writers, such as Kensaburo Oe, winner of the Nobel Literature Prize, and Naoki Matayoshi, winner of the Akutagawa Ryunosuke Award. What Mao seeks to achieve is to become a bridge between the two cultures and foster mutual understanding.

As Naoki Matayoshi said after his visit in China in 2017: "We should focus on what we have in common, where there is a light of hope."

Editor: Li Qiaoqiao