Wang Jiayang passed away on January 19, 2020 at 102. I worked as editor-in-chief of Cultural Dialogue under his guidance for ten years after I stepped down from the leadership of Zhejiang Daily Press Group.

Born into a poor rural family in Ninghai in 1918, Wang Jiayang arrived in Shanghai and went to school there when he was 11 years old. His elder brother Wang Yuhe, 15 years senior, took care of him. They lived in a house in Jinyun Lane. Lu Xun had used to live in the same house before he moved somewhere not far from the lane. As his big brother was a friend of Rou Shi (1902-1931), an author who was a friend of Lu Xun, Wang Jiayang knew Lu Xun personally. On January 17, 1931, Rou Shi had lunch at Wang’s home and then left. But he never came back. A member of the Communist Party of China, Rou Shi was arrested with some young writers. Rou Shi wrote Wang Yuhe two letters from jail. The letters were actually meant for Lu Xun. The elder brother delivered them to Lu. Rou and four other young writers were secretly executed 20 days later. After Rou died, Lu Xun, Wang Yuhe, and some natives of Zhejiang set up an education fund for the three children of Rou Shi. One day, Lu Xun came to visit Wang Yuhe. Wang Jiayang opened the door to the visitor. As his elder brother was not home, Lu Xun didn’t stay. He left 100 silver dollars and asked him to pass them on to his elder brother.

Wang Jiayang joined the New Fourth Army in 1938 and became a member of the Communist Party of China in 1939. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Wang Jiayang worked as a secretary at the secretariat of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions and president of Zhejiang People’s Political Consultative Conference. He retired in 1994.

Before and after his retirement, Wang Jiayang did three things that will surely go down in history.

First of all, he was the founding father of Shuren University in Hangzhou. In 1984, he started to set up the university as a private education institution. Such an institution had not been heard of after 1949. He contributed a great deal to the founding and smooth operation of the university. He helped solve many problems in the first few years of the university. Thanks to Wang, Shuren University has grown into one of the best private universities on the mainland.

Secondly, Wang was vitally instrumental in the founding of China International Tea Culture Institute. Wang was no tea drinker before he was transferred back to Zhejiang. After he was back in his home province, he had close contact with tea and learned a great deal about the role Zhejiang played the national history of tea cultivation and history and culture. He initiated a proposal and eight tea-related institutions in Hangzhou responded most warm-heartedly. After preparations of six months, Hangzhou hosted the First China International Symposium on Tea Culture, attended by tea-related professionals, experts and scholars including those from China, Korea, Japan, the United States. Wang presided at the symposium. Three years later, China International Tea Culture Institute came into being with the approval of the central government and thanks to Wang’s proposal and contribution. Wang was elected to be the president of the institution. He presided at the first six symposiums on tea culture respectively in Hangzhou, Changde, Kunming, Seoul, Hangzhou and Guangzhou. Thanks to Wang, Shuren University set up a tea culture major, the first of its kind in China. In 2013, he was honored with Award of Person for Outstanding Contribution to Tea in the World.

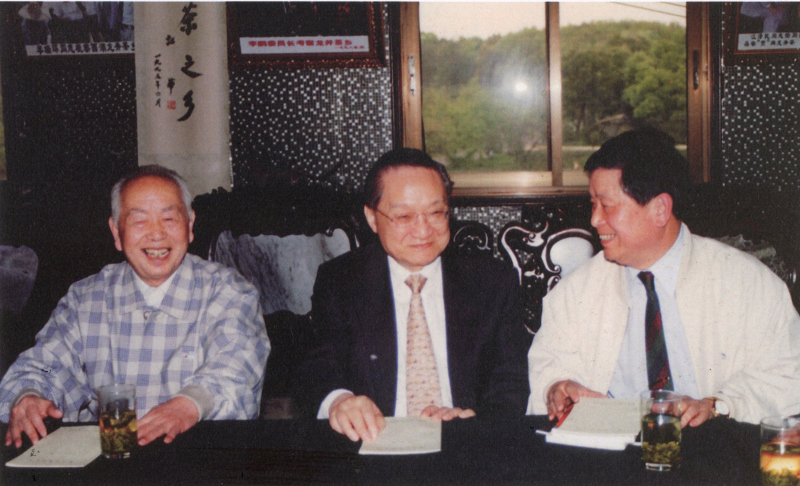

Thirdly, Wang brought Cultural Dialogue back. Cultural Dialogue was set up in 1985 by Liu Dan, then vice president of the Standing Committee of Zhejiang People’s Congress. The quarterly ran into difficulty not long after its launch. In 1987, Wang Jiayang took it over, believing it would be a pity if the bilingual publication, designed to promote Chinese culture in the world, failed. He raised funds and set up the editorial board and associated Cultural Dialogue with Zhejiang Association for Cultural Exchanges with Foreign Countries and Zhejiang People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries as two sponsors. Specifically, he engaged Wu Yaomin, who had just retired from a press job, to be editor-in-chief for the magazine. Wang was instrumental in turning the quarterly into a bimonthly. In 2000, I became editor-in-chief of the publication and reported to Liu Feng, Shen Zulun and Wang Jiayang. For ten years, they attended the year-end meeting to examine the work in the past year and look forward to the next year. They contributed ideas and topics to management and reportage.

In the first three years of the decade I worked as editor-in-chief, I was also engaged in some work at Zhejiang Daily Press Group. One day, Wang Jiayang asked me to visit him. We had a conversation. He held my hand for a long time and asked me to focus on Cultural Dialogue. I immediately realized that he was criticizing me for not spending adequate time on running Cultural Dialogue. I was deeply touched by his gentle approach.

October 2005 saw the 20th anniversary of Cultural Dialogue, which was still a bimonthly then. We received a letter of congratulation from the chief of the CPC committee of the province. The letter was reprinted in the sixth issue of the year. Wang was very happy and urged us to “give full play to the window on international exchanges and keep improving the publication”, as instructed in the letter of congratulation. At the year end of 2005, we proposed to upgrade the bimonthly to monthly. Liu Feng, Shen Zulun and Wang Jiayang supported the proposal. They helped make financial arrangements so that the monthly had adequate funds.

On October 25, 2007, I visited Wang and reported my work at Cultural Dialogue. After the report, Wang reminisced about Lu Xun and Rou Shi he met when he was very young. I jotted down the details and later fleshed them out in a report. Wang proofread the manuscript and made 20 plus corrections. It was printed in the January 2008 issue of Cultural Dialogue and caused a stir among readers. It was reprinted in other publications.

In early 2020, I was about to send out a copy of my new book to Wang when I learned that he had just passed away. How grieved I was! On January 22, I received a text from the children of Wang Jiayang. They followed their father’s will that partly reads “Simplify funeral arrangements. Disturb nobody. Don’t keep bone ashes and scatter them in a tea plantation.”