My plane arrived at Narita Airport, and I was welcomed by the homey, Japanese greeting, “お帰りなさい” (“Welcome back home!”) together with “Welcome to Japan!” in English. Well, it all depends on how a visitor takes it – the Japanese surely prefers the more heartwarming way in their own language.

This was my revisit to Japan about half a year after I came back from an exchange students program, but the eight-day stay felt like an eye-opening experience again.

The theme of the program is China-Japan collaboration in forest planting, with disaster prevention education forming a key part of the activities set in different venues. The pictures and slides shown at a meeting on the first day of the program made me tearful, although I had never been a witness to any natural disaster, not to mention the ferocity of a tsunami.

At the Tokyo Ringkai Disaster Prevention Park we visited after the meeting, we learned a lot about how Japan’s disaster prevention education starts with children. The visit also set me thinking about what we can do as college students.

For me, the most exciting part of the program was the tree planting activities in Shizuoka. The tree planting exchange program I took part last year with a group of Japanese students in Inner Mongolia sowed seeds of goodwill in me, making me look forward to more opportunities of making the world a greener and better place. In Shizuoka, my dream came true when I planted some pine seedlings into the seaside soil. For me, it was a moment of enlightenment that made me a better person than I was before.

Japan is widely defined as an aging society suffering from the flagging spirits of young generations. The eight-day revisit to the country, however, made me reconsider such a conclusion. The real Japan must be experienced first-hand. What I saw during the eight days was a high-spirited young generation pursuing creativity, independence and love. Seeing is believing. The truth is, what I saw in the majority of the old people in Japan is passion for contributing to the society, making progress, and love for life. Such passion for a sense of fulfillment was vividly shown in the Japanese representatives we spent the eight days together. They try their best to learn and make the best of their specialization and talents to contribute to international exchange and introduce Japan to people from other cultures. They all do a wonderful job in maintaining youthful vigor and curiosity about new things. In my eye, the Japanese people know better than many others about the meaning of “it is never too late to learn”, and their unfailing pursuit of excellence is amazing.

One of the venues for the activities in Shizuoka is the Nursing School of Juntendo University, where we had a good chat with a group of Japanese girls who were at first too shy to strike up a conversation. I also made a lot of new friends at an exchange meeting held in Tokyo which pulled in about 500 participants from China and Japan. The communication turned out excitingly multilingual, with Japanese, Chinese and English all used. The outgoing personality of the younger generation of Tokyoites impressed me.

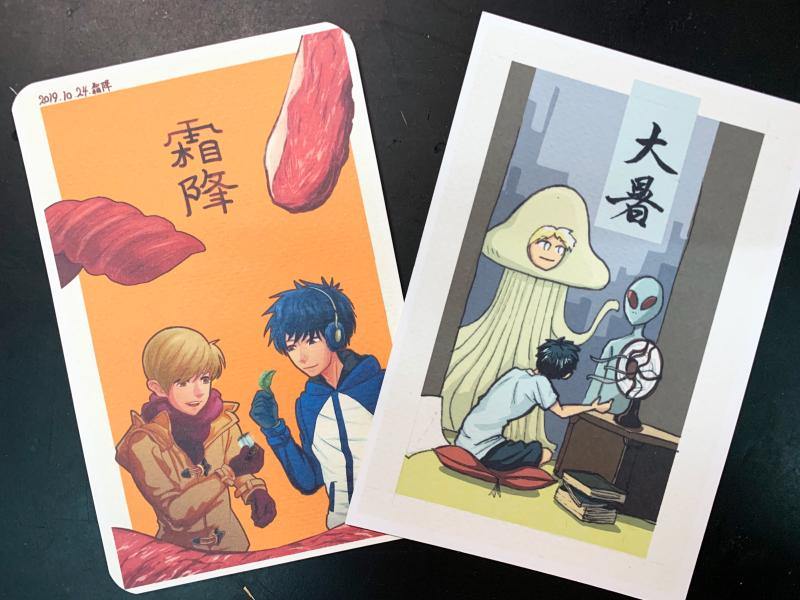

The highlight of the gathering was a set of hand-drawn postcards given by a Japanese student to me as a gift. The theme of the postcards is Chinese solar terms, which is also what I chose as the gift for my Japanese friends. The coincidence felt beautiful and meaningful.

Japan is known among people in other countries for its stereotypical “obsession” with details. It is a country that never gets tired of pursuing the beauty of even the smallest details, whether it is what’s cooked in the kitchen or the bonsai arrangements in the courtyards. The Japanese way of the pursuit of a life with aesthetic enjoyments is second to none.

That Japanese are fastidious about details was proved time and again by the arrangements of the eight-day program. To describe the itinerary of each day as “precise” is an understatement. The more I learn about the Japanese people and their culture, the more I understand why punctuality is so important in the Japanese culture and why showing up late at work is a taboo. For Japanese, being polite means behaving oneself and making room for the conveniences of other people. In the Japanese culture, time management almost serves as a cornerstone of an orderly society in which everything functions precisely.

At the end of the revisit, I was back in Narita Airport again, my heart filled with warmth again when I saw “お気を付けて行ってらっしゃいませ” (“Wish you have a safe trip.”) I will be back here soon, I thought to myself.