千百年来,江南在文人笔下,是“美”“诗意”的同义词。

江南是杏花桃花相间开的江南,是烟雨惆怅的江南,是多情的江南。

江南人杰地灵、山青水秀,不仅以鱼米之乡、风景秀丽著称,重文也是传统之一。

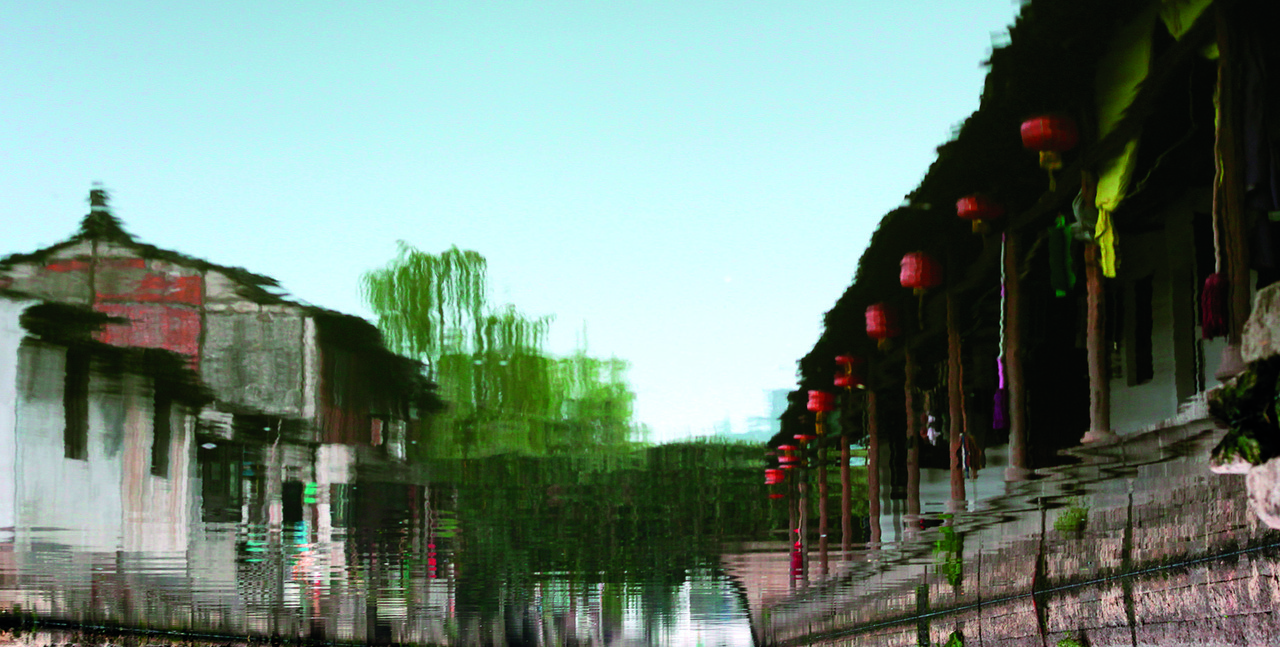

江南文化丰富多样,底蕴深厚。从白墙青瓦、小桥流水的经典建筑风格,到乌篷船、青花瓷、油纸伞,到龙井茶、紫砂壶……别有一派恬静清新、温婉内秀的韵味。

那么在一代名家的眼里,江南是一幅幅怎样图画呢?

一条河:人家尽枕河

晚唐诗人杜荀鹤在《送人游吴》中描述了当年苏州(姑苏)的情景:君到姑苏见,人家尽枕河。

“人家尽枕河”是江南城市和市镇普遍的景观。在江南小城镇上,最常见的景观便是市河,以及市河两岸“枕河”的人家或店铺。市河,也成了现代江南小城镇文学中经常出现的意象。

钱谷融先生在《〈江南味道〉序》中写道:

江南是水乡,到处溪涧纵横,绿草如茵,景色十分清幽。水是流动的,象征着江南人的活泼、富有生命力。可江南的水,少有汹涌奔放的气势,只是长年潺潺汩汩地流淌着,培育出江南人特有的温和柔美的性情。

茅盾的散文《大旱》,讲述的是大旱年头一个小小乡镇里的故事,不过这个市镇“有北方的二等

县城那么热闹”,却又比北方的县城来得“摩登”。当然,最具特色的是市镇上的市河:

镇里人家要是前面靠街,那么,后面一定靠河;北方用吊桶到井里去打水,可是这个乡镇里的女人永远知道后房窗下就有水;这水,永远是毫不出声地流着。半夜里你偶然醒来,会听得窗外(假使你的卧室就是所谓靠河的后房)有咿咿哑哑的橹声,或者船娘们带笑喊着“扳艄”,或者是竹篙子的铁头打在你卧房下边的石脚上——铮的一响,可是你永远听不到水自己的声音。

江南人自古“以舟为车,以楫为马”,船是主要的交通工具。市河自然是江南小城镇上的“交通要道”。而且河水是“活”的,在缓缓流动中,垃圾都沉淀了。

江南水乡,从吴越国时期,就开始通过罱河泥来积肥料。市河中的淤泥,分解了更多的有机物,比普通的河泥肥沃,故四乡的农民乐于到市河里来罱河泥。像茅盾短篇小说《水澡行》的财喜等农民,都是城镇保洁的“义工”。

旧时江南水乡人家,家家都有一口水缸。大清早市河里的水没有受到污染,清澈甘冽。挑水的人一般都起个大早,把水缸里的水给挑满。

郁达夫的故乡富阳县城,滨临富春江。比起市河来,从富阳县城眺望富春江,江景自然显得开阔明丽。郁达夫的短篇小说《纸币的跳跃》,描述主人公文朴回到故乡老家,次日早晨醒来,凭窗看见熟悉的江景:

绝大的一轮旭日从东面江上濛濛地升了起来,江面上浮漾在那里的一江朝雾,减薄了几分浓味。澄蓝的天上疏疏落落,有几处只淡洒着数方极薄的晴云,有的白得像新摘的棉花,有的微红似美妇人脸上的醉酡的颜色。一缕寒风,把江心的雾网吹开,白茫茫的水面,便露显出三两只叶样的渔船来。朝阳照到,正在牵丝举网的渔人的面色,更映射得赭黑鲜明,实证出了这一批水上居民在过着的健全的生活。

小说中的主人公文朴,是一位贫病交加的现代“寒士”。在外漂泊多年,不能衣锦还乡,回到老家来可谓悲喜交集。不过老家的江景还是赏心悦目,富于诗情画意。

四季花:只嫌春光短

江南水乡,属亚热带季风气候,四季分明。春夏秋冬,在小城镇的花木意象中得到充分体现。

丰子恺在散文《辞缘缘堂》 中就回味了缘缘堂五年生活中的四季风情:“春天,两株重瓣桃戴了满头的花,在门前站岗。门内朱楼映着粉墙,蔷薇衬着绿叶。院中秋千亭亭地立着,檐下铁马丁东地响着。堂前燕子呢喃,窗内有‘小语春风弄剪刀’的声音。”“夏天,红了樱桃,绿了芭蕉,在堂前作成强烈的对比,向人暗示‘无常’的幻相。葡萄棚上的新叶,把室中人物映成绿色的统调,添上一种画意。垂帘外时见参差人影,秋千架上时闻笑语。”“秋天,芭蕉的叶子高出墙外,又在堂前盖造一个天然的绿幕。葡萄棚上果实累累,时有儿童在棚下的梯子上爬上爬下。夜来明月照高楼,楼下的水门汀映成一片湖光。”“冬天,屋子里一天到晚晒着太阳,炭炉上时闻普洱茶香。坐在太阳旁边吃冬舂米饭,吃到后来都要出汗解衣服。廊下晒着一堆芋头,屋角里藏着两瓮新米酒,菜橱里还有自制的臭豆腐干和霉千张。”

鲁迅的回忆性散文《从百草园到三味书屋》,也写到百草园和三味书屋后面的小院子里的四季花木:春天“肥胖的黄蜂伏在菜花上,轻捷的叫天子(云雀)忽然从草间直窜向云霄里去了”;初夏有“紫红的桑椹”,盛夏有“鸣蝉在树叶里长吟”;秋天,“木莲有莲房一般的果实”,还有“油蛉在这里低唱,蟋蟀们在这里弹琴”。冬天的百草园比较无趣,不过三味书屋后面的小院子里的腊梅盛开了,“可以爬上花坛去折腊梅花”。

徐志摩的小说《家德》写了当年徐家的帮佣家德。他中年时就来到徐家,一直做到了老。家德勤劳、博学,徐家后面那个“花园”一直由他操劳。他在这个花园里种菜,也种花木。初春有春梅和兰花,阳春有桃花、李花和玫瑰,夏天有美人蕉、凤仙花和硕大的鸡冠花,秋天有蟹爪菊,冬天有腊梅和山茶花。月季更能开上大半年。小说中的家德简直就是种花专家,能给儿时的“我”讲解各种花草的知识:“花的脾,花的胃,花的颜色,花的这样那样。梅花有单瓣、双瓣,兰有荤心、素心,山茶有家有野”。

朱自清祖籍绍兴,但青少年时代生活在扬州,故自称是“扬州人”。朱自清在散文《看花》中讲述自己从小生长在扬州,扬州人爱花,几乎每家都有几盆花。该文还写到作者刚出大学校门时与俞平伯在杭州共事,冬天经常去孤山放鹤亭赏梅,有一回还专门去灵峰寺探梅。日后两人又在清华大学共事,春天两人先后去中山公园欣赏海棠。与江南相比,北平春短,赏花要赶着时间去。“他说北平看花,是要赶着看的:春光太短了,又晴的日子多;今年算是有阴的日子了,但狂风还是逃不了的。”相比较而言,四季分明的江南可以从容欣赏四季不同的花。

小镇子:城门四面开

江南小城镇上的市民,尽管在造桥、铺路时采用石材,但在建造房屋时石材只作为辅材,房屋的主体是砖木结构的。

城镇上的市房,是要开门做生意的,砖木结构的房子便于开门迎客,又便于分隔,开店住家都方便。鲁迅的短篇小说《孔乙己》,开头就描述了咸亨酒店的格局:

鲁镇的酒店的格局,是和别处不同的:都是当街一个曲尺形的大柜台,柜里面预备着热水,可以随时温酒。做工的人,傍午傍晚散了工,每每花四文铜钱,买一碗酒,——这是二十多年前的事,现在每碗要涨到十文,——靠柜外站着,热热的喝了休息;倘肯多花一文,便可以买一碟盐煮笋,或者茴香豆,做下酒物了。如果出到十几文,那就能买一样荤菜,但这些顾客,多是短衣帮,大抵没有这样阔绰。只有穿长衫的,才踱进店面隔壁的房子里,要酒要菜,慢慢地坐喝。

像咸亨酒店这样的临街店面,早上卸下排门板,就能开门迎客;晚上推上排门板,店里的掌柜和伙计就能关门睡觉。

茅盾的短篇小说《林家铺子》所写的林家杂货店,是家连店的。当街为店面,一对蝴蝶门后就是林老板家的“内宅”。内宅有楼上楼下两层,楼上卧室,楼下厨房和吃饭间。

另外,小城镇上还有一些前店后坊的手工作坊。如丰子恺的石门老家,有百年老店丰同裕印坊。当街的惇德堂主要作染坊用,门前还要晾晒染好的布料,主人家住在后面几进的房子里,店里的伙计就住在店里。

明清至民国时,江南小城镇上,一般人家住在临街的房子里,而大户人家则居住在相对安静的深宅大院里。

茅盾的长篇小说《霜叶红似二月花》中,张恂如家在街面上有“源长号”广货店,经理宋显庭和儿子宋少荣、学徒赵福林等就住在店里,张家另有豪华的住宅。小说描写了张家府上有高大的“风火墙”,是徽派建筑典型的“马头墙”。旧时砖木结构的房屋容易引发火灾,而且一烧就是一大片房屋。高大的“风火墙”,容易隔断火灾,不至于邻居失火殃及本宅。马头墙的“马头”,通常是“金印式”或“朝笏式”,显示出主人对“读书作官”这一理想的追求。“马头”既是一种美观的装饰,同时也是一种官本位思想的图腾。

江南潮湿,讲究的人家卧室一般安排在楼上,这也是从新石器时代干栏式建筑传承下来的。张府的二楼是“走马楼”,即四周都有走廊可通行的楼屋,特别适合大户人家居住。不过张府人丁不旺,只有张恂如一个男人。他大学毕业后赋闲在家,郁郁不得志,只能在家里作些小小的反抗。他对妻子有些讨厌,就搬到三间平时堆放杂物的平房里去住。一般情况下,大户人家的一楼平房是下人居住的。徐志摩的小说《家德》中徐家的帮佣家德就住在一楼。

徐迟的抗战小说《一个镇的轮廓》发表在陆丹林主编的《大风》半月刊第76、77、78期,出版日期为1940年7月20日、8月5日、8月20日。该小说写了近代丝商富豪云集的南浔镇。综述了那些精心构筑的私家花园:

富绅没有不是以丝起家的,小小一个镇,有着十几个上千万,上百万富翁。因此,镇上有四五个花园,是文化的结晶:亭台楼阁,花木掩映,诗,画,碑帖,对联挂满。每年只有清明佳节日,开放游览一天。到那天,满园满林是踏青人,乡下人也穿上了漂亮新衣服来玩。

至于江南小城县的形制,即建筑格局,往往是市镇有四栅,小城县有城墙乃至护城河。小城镇主要的功能是交易,但也有防御功能。

郁达夫的短篇小说《盂兰盆会》写了在东山半山腰圆通庵回望不远处的县城:

山脚下是一条曲折的石砌小道,向西是城河,虽则已经枯了,但秋天的实实在在的一点芦花浅水,却比什么都来得有味儿。城河上架着一根石桥,经过此桥,一直往西,可以直达到热闹的F市的中心。

在这里,富阳县城的护城河以及石桥,很好地体现了县城的功能。城河是护城的,体现了防御功能;石桥是通向县城的,通过此桥可以到城里交易。

有些小城市只有城墙,没有城河。施蛰存短篇小说《进城》收入作者的第一个小说集《江干集》,于1923年自费出版社。作者自谦为“青少年时代的描红练习”。该小说就描写了这种没有护城河只有城墙的县城。

江南水乡,船只是主要的交通工具,故城门往往有旱门又有水门。周作人在1940年代专门写了小品文《绍兴城门》,介绍绍兴的城门:

绍兴城旧有九门,据尹幼莲《地志述略》所举俗称如下,即东郭,都泗,昌安,西郭,偏门,南门,稽山,五云,雷门是也。前六门皆是水门,平时拜岁扫墓都曾走过,余乃是旱门,雷门早封闭,今只余地名罗门坂耳,五云俗呼作吴市门,茹三樵云即梅福故迹,稽山门则是至禹陵会稽山之要道,出入尤频繁……此诸城门中最系怀念者为东郭,不但与祖居相近,时常出入,其地亦特僻静,每当黄昏时入城来,城楼半废,墙上满生薛荔,四望荒凉,城内与城外如一,颇有诗味画意,非南门等所能有也。昌安偏门等水门外别有旱门通行,南门独否,出城者须趁渡船,官设不取资,东郭则沿城门有石墈,可以步行,出门即渡东桥,相传第三洞下流水是神仙水,又为明末余武贞先生殉难处,唯后人都已不甚了了,只于大旱时至桥头取水以供茶饭而已。

有了城墙和城门作为防御设施,到了晚上,城外的人很难进城,城内人也同样不容易出城。鲁迅的小说《阿Q正传》,写阿Q沦为小偷,由于合伙行窃时“正手”被人发现,在外应接的阿Q吓得赶紧跑,“连夜爬出城,逃回未庄来了”。鲁迅描写的“爬”,显然是指翻爬城墙。

跟小城市相比,市镇的防御系统就比较弱。市镇是没有城墙护卫的交易场所。江南水乡,强盗们一般是摇了船抢劫的。防御之法,是在进入市镇的市河口上设置栅栏,晚上关闭栅栏,防止强盗船只进入。这就形成了“市栅”。像乌镇那样两条市河成十字交差的市镇,有东南西北四栅。

樊树志指出,四栅,“是指镇区市梢的边界,一般都有栅门,犹如县城的城门”。栅门分陆栅和水栅,陆栅设在街道的末端,在两旁民房之间砌上围墙,中间是一扇木制的栅栏门。水上栅栏门设在市梢的桥洞内。陆栅和水栅,都是清晨开启,晚上关闭,以保障镇区街道、商店和居民的安全。

徐迟的小说《一个镇的轮廓》,也写了这个镇“东南西北有四个栅,真有栅栏的,并不是名义上的存在的呢”。

(本文图片提供:CFP)

For the past centuries, Jiangnan has presented an unparalleled beauty in Chinese poetry and prose. Some descriptions are so popular that whenever someone wants to describe Jiangnan they pop up: Jiangnan is where apricot and peach flowers bloom; Jiangnan is where people feel sentimental and somewhat lost when it drizzles and mists; Jiangnan is where romance happens. Jiangnan is famed for prosperity, history, culture, artists, scholars, poets.

Rivers in Jiangnan

Du Xunhe, a poet (846-906) of the Tang Dynasty, wrote in a poem dedicated to a friend heading to Suzhou, a legendarily wealthy city in Jiangnan that there were so many rivers in Suzhou that residents there had a river by their pillows. It is true that in the past, towns and cities in Jiangnan were crisscrossed by rivers and boats were the major means for people to move around.

“Jiangnan is a world of waters. Creeks and rivers are everywhere. Grasses are as thick as carpets. The landscape is quiet and elegant. Waters are full of life, symbolizing the vigor and life of people in Jiangnan. The waters in Jiangnan rarely show an overwhelming momentum. They just flow dreamingly all the year round, giving birth to a tender temperament native to people in Jiangnan,” wrote Qian Gurong (1919-2017), a theorist of literature and art, in a foreword to a book about Jiangnan.

Big Drought, by Mao Dun (1896-1981) depicts a rural town in a year of droughts. The town is typical of Jiangnan. All the houses in the town have a street front and a river to the back of the low row of houses. Residents there can always hear noises made by boats passing by. They don’t hear the sound of the river itself. Unlike their counterparts in the north who fetch water out of a well, the residents in the town get water from rivers.

In Jiangnan, boats used to be the main transportation means. A market river was always the mains street of a river town. In ancient times, rivers in Jiangnan were regularly dredged. The bottom mud dredged from rivers was used as a fertilizer for rice paddies and vegetable plots. Rural residents liked to dredge rivers in towns largely because these rivers had better bottom mud. Also in good old days in Jiangnan, each house had a large water vat. Residents got up early in the morning and fetched water from rivers.

In , a short story penned by Yu Dafu (1896-1945), a young man who fails to make a career and comes back to his home village by a river. The river portrayed in the short story is the Fuchun River zigzagging past the writer’s hometown Fuyang. “The giant sun rises in the east, dissipating the thick mist hanging low on the river. The blue sky is dotted with some thin clouds, whitish and pinkish. A cool breeze drives the mist away, revealing some fishing boats, which look like slender tree leaves. The morning sunlight on the faces of the fishermen shows that these people lead a healthy and complete life on the river.”

Trees and Flowers

Jiangnan is a paradise of flowers thanks to the four distinct seasons characterized by the subtropical monsoon climate.

Feng Zikai (1898-1975), a cartoonist and essayist, wrote in an essay titled about the flowers and trees around the house in his five-year stay there. “In springtime, two peach trees bloom furiously\ in front of the house. The roses bloom. In the summer, cherry trees and banana trees in the front garden present a sharp contrast in reds and greens. In the autumn, the banana trees are taller than the compound wall and form a huge screen in front of the house. The trellis is full of the grapevines, grapes hanging in clusters.”

Lu Xun (1881-1936) recalls roaming in gardens in his childhood years: “In springtime, fat bees sit on the vegetables. A lark darts into the clouds from the grass. In the early summer, the mulberry trees bear purple berries. In the hottest summer days, the cicadas sing incessantly in trees. In the cold days in January, wintersweet flowers are in the small garden behind the school house.”

Xu Zhimo (1897-1931), a poet of modern times, wrote about a gardener named Jiade. He came to his family to work as a help when he was still a middle-aged man and he worked there until he was very old. The man took care of the garden in the back of the house, where he grew vegetables and planted trees. Xu Zhimo grew up there, learning a great deal about flowers, trees and vegetables from the man.

Zhu Ziqing (1898-1948) grew up in Yangzhou, a city just on the northern shore of the Yangtze River. He had his ancestral roots in Hangzhou. In an essay titled , he wrote that the people in Yangzhou loved to keep flowers at home. In addition he wrote about outings he took with friends to watch flowers in Hangzhou and Beijing.

Architecture

In towns across ancient Jiangnan, stones were used to build roads and bridges. Houses were largely made of brick and wood. Many houses in river towns had a shop in the front. A structure of brick and wood was easy for opening the door wide to customers. Such a shop front had an old-styled door as wide as the shop front. The door was composed of wood boards that could be removed at the opening hour of business time and installed back to form a closed space inside at the end of business time. Some shop attendants lived in the shop. The back part or upstairs of the house could easily be used for the family to lead a private life.

In the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911) and the years of the Republic of China (1911-1949), most town people lived in street houses in Jiangnan. Only big families lived in a house within a large walled compound. And many houses were two-storied structures as the second floor stayed relatively dry in a wet climate in Jiangnan. In very primitive times, stilted houses were popular in present-day Zhejiang, as discovered by archaeologists.

Some river towns in Zhejiang had river fences for safety at night. A fence could be lowered into a river in the evening and elevated out of water in the morning. Such fences formed a security network and stopped anyone from entering or leaving a town at night. Take Wuzhen in northern Zhejiang for example. The town has two main rivers that crisscross the town. In the past, four river fences defended the town in four directions and kept brigands or thieves away at night. Some river towns had fences in streets. The fences worked as gates at night. Walled cities such as Hangzhou and Shaoxing in the past had both land gates and water gates.