柳永的江南,是有三秋桂子,十里荷花的钱塘盛景;张养浩的江南,是一江烟水照晴岚;杜牧的江南,是千里莺啼绿映红;张继的江南,是夜半钟声过江来;韦庄的江南,是记忆中皓腕凝霜雪的卖酒姑娘……

这时的江南,是一个名词。

如果将江南看成是一首诗,这至少会得到杜甫、白居易、张若虚、杜牧、柳永、苏东坡等一流诗人的支持。同样,在张继、寒山等一些诗人的作品中,江南也还是可以伸手触摸到的。我相信江南就是由这些诗人用一些特定的语言发明出来的。这个可以触摸的江南大抵由以下的词语构成:塔、杏花、春雨、满月、杨柳、旧桥、寺院、石板弄、木格子花窗……当然还有少不了的碧绿的水。

这是一个名词的江南,它完全可能是一次语词的盛宴。这些语词成了江南的手、胳膊、腰板、小腿肚……乃至大脑,也就是说,江南首先是活生生的——一个不施脂粉的少女。

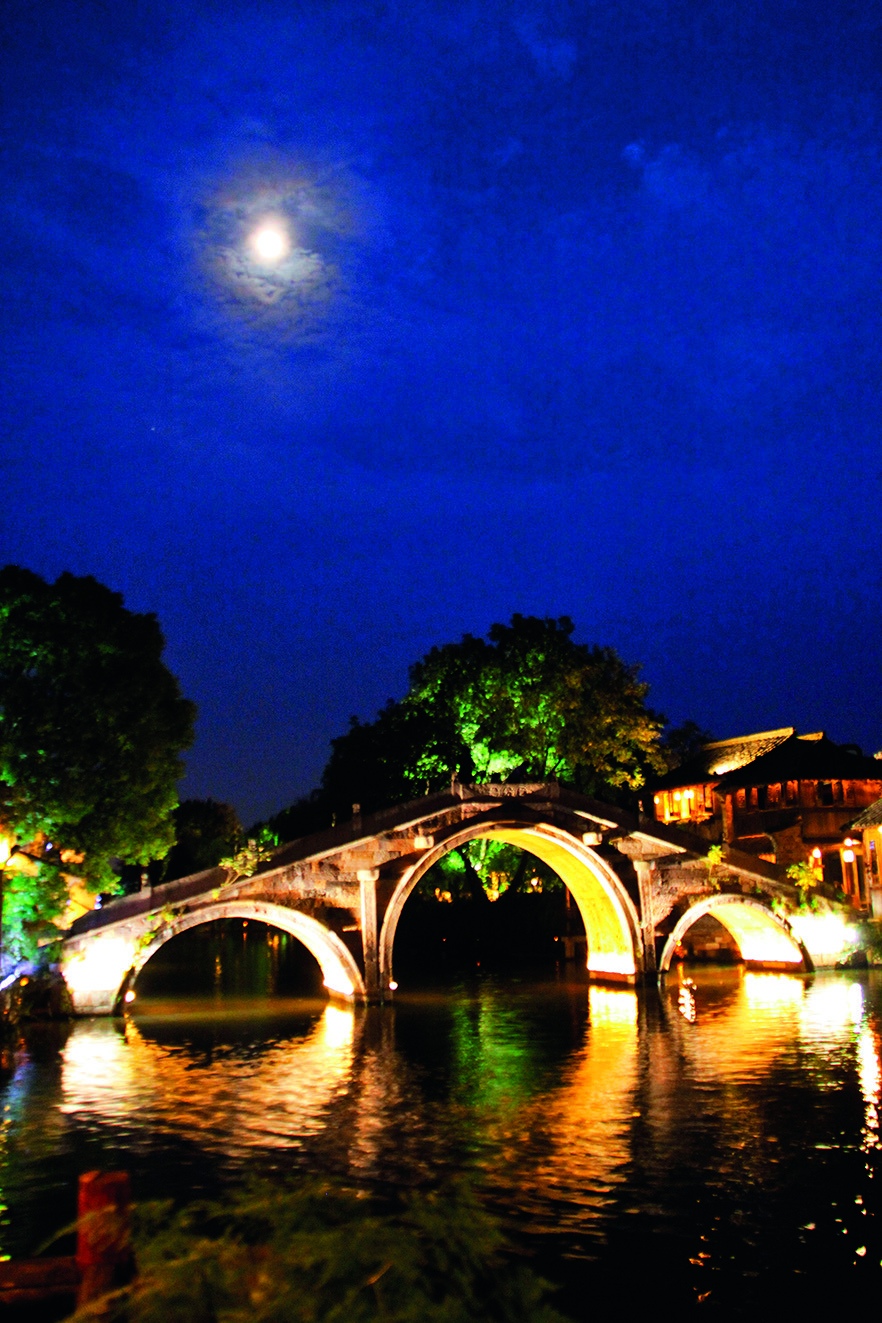

自然,我们不会忘记这个少女是有一双特别明亮的眼睛的。这双眼睛有一个清澈的名字——明月。即使后来我们的身体已不在江南了,当我们身处异乡随口念出这个充满柔情蜜意的词语时,一轮明月马上就会降临在我们眼前。江南,正是因为有了明月,它才显得特别地容光焕发,它才会从泥淖之中拔出光洁的身子,成为一个精神性的文化意象。

从一个又一个具体可感的名词开始,江南这一首抒情诗就日渐丰盈起来了,并且像所有的诗歌一样,诗的美妙的第一行给了我们一个方向,那就是:从长江开始,追随着温润的植皮,一路往南……紧接着的那个空间是多么辽阔,我无法想象它的最后一行该在哪里结束。幸好作为具体的诗行在这里已经不重要了。江南以无比的耐心捧出了时间深处珍贵的册页——它保存着令人眩晕的花香、鸟语、节气、光速、亡灵的叮嘱;保存着清水中的荷叶、荷叶上的露珠、露珠上一只突然逗留又突然展翅飞离的蜻蜓;它还无可怀疑地保存了门楣上的铜绿、青石板上的苔藓、独眼的石狮子的自尊以及朴实的人民水滴石穿的韧性。

江南最后进入一个词,一个像苹果一样掷地有声的名词。在它最接近生命的那个果核里,我想献出的是一册《江南词典》。

江南词典

如果在酒类中找出一种契合江南人性格的品种来,既非性情火爆的白干,也非浑浊暧昧的米酒,更不是带着翻译口味的葡萄酒,而几乎——肯定——是黄酒。

首先是它的颜色,黄酒的暗黄,那是全体中国人民皮肤的颜色。最初的造酒师傅一定洞悉了空气、皮肤与水的关系,才造出了那么一种与劳苦大众的脸庞相呼应的性格鲜明的中国酒。不用问,百家姓里,黄酒自然姓黄,是一种有着绵长时间概念的暗黄;是一灯如豆,映在原木家具上的暖色调的黄;一种草黄,而非紫禁城里富贵至尊华美雍容的黄金的黄。

“菰正堪烹蟹正肥”(陆游)的时候,村场酒薄,光膀赤膊,点几粒花生米,呷一小口一小口的黄酒,酒力泛滥,一醉又有何妨!

黄酒的中心是绍兴。绍酒天下名。说黄酒,不说到绍兴是怎么也说不过去的。袁子才(注:袁枚,字子才,清代文学家、美食家,晚年自号随园老人)黄酒吃罢,撰了一张《随园食单》,其中对绍酒推崇备至,他把它比作品行高洁、超凡逸群的清官和名士。随园老人大概这一天绍酒过量,一张嘴终于彻底绵软下来,于是,冲口而出:“绍兴酒如清官廉吏,不参一毫假而其味方真;又如名士耆英长留人间,阅尽世故而其质愈厚。”总之一句话,黄酒在文人士大夫心中占据的位置至为重要。

正宗的、窖藏数十年的绍酒,总是不多见的,吾辈也极少有机会喝到。但在江南百姓的八仙桌上,在老灶头边,每家每户,至少是有一瓶包装简陋、价格便宜的黄酒——那是用于去除腥味的料酒。这时候黄酒所担当的,是和姜、葱、蒜一样的一个角色。比如,在剖开的鱼、捏好的肉丸子里兑上一点黄酒,立刻就散发一种醉人的酒香。即使某些蔬菜如茄子、丝瓜,清炒的时候兑入一些黄酒,也别有一种风味。

如果往抽象里考量,黄酒带有中国哲学里特有的颜色和气味。它宽厚、温和,似乎是为了顺应江南人的性格而发明的。它有一股中药味,入口绵软,醇厚,暖心暖胃,其酒力缓慢地上身,喝起来不会像高度白酒,感觉到喉咙里有一道火舌流过。黄酒如丝绸,是一层一层温柔地抽剥你或缠绕你,不知不觉地,你就醉在其中了——醉得如软泥一般,扶也扶不起来。故性子刚烈的北方人,是不大敢喝黄酒的。他们宁愿喝性格暴烈的白酒,也不愿喝丝绸般缠绵悱恻的黄酒。

我总以为蓝印花布的出现与某种神秘的星象图有关——白花点点的图案,撒播在暗淡的老蓝布上,蓝得浓烈,白得纯洁,好像星星的眼睛布散在神秘的苍穹之中。

其实不是,它是一次偶然的产物,是某个无名的染坊师傅失手而成的一次杰作。我甚至看到了那个无名的小师傅惊慌失措的眼神,两只无助的手臂悲哀地下垂着,还甚至揪起了自己的头发……

这个传说中笨头笨脑的染坊师傅,肯定被自己的一次失手惊呆了,被自己的粗心大意烦恼得快要爆炸了。但是,连他自己都无法相信的是,上天竟然将他的这次失误惊奇地显现成了人世间的一个奇迹。或许,许多好东西,都不是聪明人刻意的创造和发明。事物超凡脱俗的品性,反倒在无意中成就。蓝印花布的出现就是这样,是一次天意,也是中国民间文化的必然产物。它让吃惯了鸡鸭鱼肉的食客忽然吃到了一碟素炒马兰头,欣喜之情可以想见。是的,事物的幽姿逸韵,大多在它的色容之外。

蓝印花布对应着一个已逝的年代——一个用木头、青砖、油灯、团扇、青瓷、线装书、油纸伞、儒家的礼仪等等构筑起来的年代,一个将自己的青春牢牢勒紧的时代。它粗糙的手艺,是民间的,作坊里出来的;它朴素的颜色——蓝和白,来自沉稳的中年性格。深沉和略带忧郁的江南性格给了蓝印花布一个醒目的基调,既老于世故,又活泼得有点儿调皮。

一匹蓝印花布高挂在长竹竿上,仿佛静止的雪花还没有在瓦楞上完全融化的那种样子。两种本来并不怎么显眼的颜色,这会儿互相将自己衬托出来了。

在蓝印花布上,我看到了镇定的性格和灿烂的心灵,它兼有少妇的端庄和少女的顽皮。我仿佛看到前者用手掌试图捂住后者叽叽喳喳的嘴巴——而珠玉乱溅的少女的声音终于还是从指缝间漏了出来。

蓝印花布是民间的产物,据说宋代已经在江南一带出现,但它的盛行,却在明清两代,尤以江南地区最为普遍,而且,它基本上也只在江南的民间流行。因此,它没有绫罗绸缎的富贵气和霸气,总带着一点小巷子里来的山野气——有点粗糙,有点满不在乎的我行我素——好像爱美的江南女子插在云鬓里的那一枝山花,美在自然、鲜活。

穿着蓝印花布的女子行走在一个令人神往的江南——那个青石板的、水的江南,无论何时,总是和蓝天、白云、翠绿的万物相得益彰的一段风景(情)。

明月是中国最著名的一个意象。今月曾经照古人,在一页白纸上,当我将明月请出来亮相时,我知道,很多诗人就会前来争夺发明权——明月是他们用精美的中国文字擦拭出来的。如同保管一颗露珠,每位诗人空出自己的左心房,小心轻放着这一份秘密的情感。从小小的一枚月牙儿到一轮丰满的圆月,一位又一位诗人,端起酒杯,睁着一双痴迷的眼睛,咬文嚼字,浮想联翩。

因为遥远,也因为它的高度,人们编造了很多美丽的传奇。明月让我们民族的想象力有了一次出色的跃升。在谢灵运的木屐无法攀登的地方,伟大的诗人们用想象力攀上了尘世风景的顶峰。这个古往今来挂得最高的意象,无疑,也是中国诗人攀登次数最多的一个地方——一行行有关明月的诗歌,筑成了中国诗歌史上极为重要的篇章。明月给了中国古典诗歌清冷的气息,以及高贵和独一无二的品质。这些神仙似的分行,温润如同一颗夜明珠,简洁犹似一个发着银光的惊叹号,在浩瀚的宇宙里,它一次次让我们无言。

明月最适宜在江南出没,天下三分明月夜,二分无赖是扬州。扬州,或者我愿意稍稍扩大一点,整个江南就是明月的娘家。当明月经过马头墙,经过长廊,经过私密的后花园,爱情就发生了。它逗留在瓦楞上,在树梢间,在澄澈的水里,在宇宙的中心,一个地方一个影,决不重复。

明月是唯一的,又是无穷的,每一位中国人都保存着这么一份月圆与月缺,都拥有一张悲欢离合的时刻表。我有时觉得,只有经过明月抚摸过的事物,才会神圣而魅力四射。明月夜,短松冈,自李太白捞月身亡几百年后,它又一次在苏东坡的手里大大地放了一回光。明月见证了诗人的一段生离死别,也见证了寻常百姓的悲伤和欣喜。

当你用念珠般光洁的汉字擦拭明月时,明月悄悄地收走你满脸的悲伤。它是我们时代最有风度的旁观者。它和谁都保持着一种亲密的关系。它无声地搬走我们的青春,沧海桑田,自己却从未见老……无论何时,只要我们在它的面前朗诵起诗歌,我想它仍是一位珍贵的倾听者。和许多我们敬畏的事物一样,明月以金子般的无言,默默地注视着你。它将一捆捆赞许的光线,扎紧了,扔到熊熊燃烧的篝火上,鼓励你将歌颂明月的窈窕之章朗诵得大声一点,再大声一点,更大声一点……直到时间屏住翅膀。

(本文图片提供:CFP)

Jiangnan, which now refers geographically to the south of the Yangtze River Delta, can be considered a poem. This proposition could be supported by poets of the Tang (618-907) and the Song (960-1279) whose names come down in the history of Chinese literature. In poetry and prose, Jiangnan is portrayed in a vocabulary composed of such nouns as pagodas, apricot blossoms, springtime drizzle, the full moon, willows, old-time stone bridges, temples, stone-paved lanes, lattice windows, rivers and ponds. Jiangnan is a world of nouns.

These nouns capture and convey what Jiangnan means to people. One could follow these nouns from the southern shore of the Yangtze River. The southward journey reveals pages written with bird chirps, weather, sunlight and moonlight, flower fragrance, whispers from the dead, dewdrops on lotus leaves, a dragonfly that hovers upon a lotus leaf and then suddenly darts off, a door with two copper knockers, green moss on a stone slab, a damaged stone lion with dignity intact and awe-inspiring, a simple lifestyle that persists against all tribulations.

A dictionary of Jiangnan is long overdue. Such a dictionary would have entries like yellow wine, blue calico, the moon, just to name a few.

Yellow Wine

The yellow wine perfectly defines the temperament of the people of Jiangnan. Local people are proud of the wine as it is the only color that goes well with the skin-color of Chinese people. Moreover, it indicates the infinity of time. It interacts intimately with the original color of wood furniture. And it is all about the grassroots life. It quietly keeps itself away from the noble golden yellow of the Forbidden City. For many people in Jiangnan, it is happiness itself sipping yellow wine and enjoying peanuts.

Shaoxing in eastern Zhejiang is China’s number one maker of yellow wine in terms of both quality and quantity. Yuan Mei (1716-1798), a literary master and famed gourmet, thought highly of the wine made in Shaoxing. He even compared the mellowness and honesty of the beverage to the ideal personality of the literati. In fact, some scholars philosophize their favorite beverage. It is mellow and warm and gentle in sharp contrast to the fast, hard and strong booze. The deceptively low wine often knocks out some unwitting hardcore boozers from the north.

The vintage yellow wine is rare and few people are fortunate enough to sip a cup. Fortunately, most brands of the yellow wine are conveniently affordable to all drinkers with a penchant for the wine. And most families in Jiangnan use it as a cooking wine.

Blue Calico

I used to believe that blue calico came from a primitive map of the night sky: white dots spread across the dark blue fabric and the pattern suggests a night sky full of stars. The dyed calico does not have such a mysterious genesis. A nameless craftsman in a nameless workshop made a mistake by accident. It is not hard to imagine how the craftsman felt desperate when realizing he had made a mistake. But miraculously, the mistake gave birth to blue calico as is known today.

History has it that the dyed fabric emerged in Jiangnan in the Song and flourished in the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911). With a long list of other old-time symbols such as wood, brick, oil lamp, paper fan, celadon, thread-bound book, oiled paper umbrella, protocol of behavior based on Confucianism, blue calico signifies a bygone era. The somewhat crude craftsmanship indicates grassroots workshops where the calico was made. The blue and white tints define a middle-age personality. The melancholy and deepness give the calico a fundamental theme. It emits an aura of worldly understanding and childlike innocence. Jiangnan is made of a lot of things and people. A girl dressed in a blue calico garment is one of them.

The Moon

The moon appeared in Chinese poetry long before Jiangnan did. But historically it was Jiangnan that made the moon so storied, so legendary, so dreamlike, and so emotionally associated with the world and private life. It would be hard to say whether it was the moon that made Jiangnan so intimately special or whether it was Jiangnan that made the moon look so poetic. When nouns come together with the moon, pictures emerge and take shape. The moon passes over a long corridor or a walled garden and love happens, as recorded in numerous stories and folktales in Jiangnan. Those who have been bathed in moonlight in Jiangnan know that the moon witnesses our personal feelings when we are hit by sorrow. A life shines only after it is touched by the light of moon. The moon travels with us. It carries away youth, changes the world, composes poems, and makes life different. Li Bai, presumably the greatest poet of the Tang, gets drowned when trying to rescue the moon out of waters. Su Dongpo sighs over his grief after visualizing the moonlight on the tomb of his wife dead for ten years, with dark pinewoods standing nearby.